This spring I had an Allen’s Hummingbird nest just outside my backyard door. Whenever I find a nest in

my yard, my first reaction is one of pure joy, but is always followed by a little anxiety. I have seen so

many nests fail. It is the way of the world, and I know this, but even observed with a scientific mindset it

is hard to not be invested. Nests in your own yard are really special.

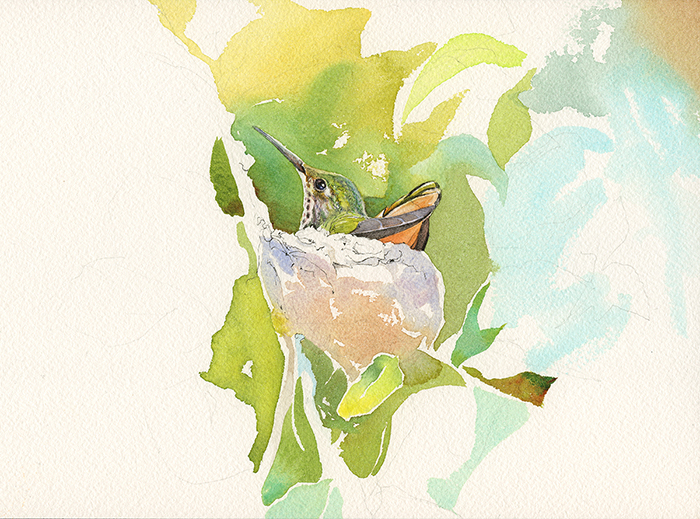

This nest was beautifully situated, visible only from one angle, ensconced in a shrub. All I could see was

the nest cup; there was no female sitting on it. I believed it was a new nest, but perhaps it was an old or

unused one that had gone previously unnoticed? Since peering into a nest can bring rather clever

predators straight to their next meal, I decided to find out if it was viable by use of a thermal camera. I’m

fortunate to have one of the ZEISS models at hand, so I grabbed my DTI and first thing the following

morning I went out to check. The female was on the nest! And the whole nest radiated red hot!

And so project hummingbird watch began. I found a spot to set up my scope for distance viewing and

sketching, and kept my hopes mediated.

Most identifications and accounts of hummingbirds start with the flashier, pugnacious males. Adult

males are visually incredible tiny packages of energy and fury, but they have nothing to do with nest

building, incubating, or rearing young. Their job is to be feisty and fabulous, and that’s it, so my nest

observations did not involve them.

While Allen’s Hummingbirds are a ubiquitous resident here, their nesting presence is the result of a very

recent range expansion. Close cousins to the Rufous Hummingbird, Allen’s Hummingbirds are far more

restricted in their range, hugging the California and Oregon coastal areas in summer and wintering in

Mexico. The nesting birds in my yard are a uniquely non-migratory subspecies, and in our Los Angeles

neighborhood, breeding data starts only in the mid-1990’s. Thought to have originated from one of

California’s Channel Islands, our Allen’s Hummingbird subspecies has spread dramatically.

Selasphorus sasin sedentaris makes for a pretty cool scientific name. Selasphorus comes from Ancient

Greek, smashing together two words to form “Flame-carrying”. Sedentaris means, of course,

“sedentary”. Sasin means ‘hummingbird’ in the language of the Nuu-chah-nulth, one of the Indigenous

peoples of what is now Pacific Northwest Canada. This bird has an interesting naming history, which is a

bit too long to go into here but brings up the current topic of eponymous naming of birds, and I

encourage anyone to research it further, for the love of history and ornithology both.

I was lucky this time; the nest had two healthy chicks who made it all the way to fledging. I watched as

the first tiny bills appeared, then two heads, then two bodies too large to fit into the nest any longer (if

one can ever describe a hummingbird as too large). Then the nestlings, one slightly larger, took off one

after the other, and were suddenly gone.

Citations:

- Allen, Larry W., Kimball L. Garrett, and Mark C. Wimer. 2016. Los Angeles Breeding Bird Atlas. Los

Angeles Audubon Society, Los Angeles, CA, USA. - Clark, C. J. and D. E. Mitchell (2020). Allen’s Hummingbird (Selasphorus sasin), version 1.0. In Birds of

the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. - Sibley, David A. 2014. The Sibley Guide to Birds. Alfred A. Knopf. New York, NY, USA.