Most birders have birds they would very much like to see but have not yet seen, ones that are

highly desired and sought after. For species repeatedly chased and missed and frustratingly

never where they should be, we grumble about nemesis birds, and hope for another try. For

rarities that show up when you are out of town or unable to twitch for work or family or financial

reasons, we bemoan missed opportunities (sometimes quietly, sometimes not). This often

leads to a feeling of not quite enough time, of always seeking the next lifer, of a constant quest

for, well, more. There other kinds of wish list species too, though. There are birds that hold

some combination of the above, but they also hover on the fringes of our imagination or

contain associations that extend beyond simple identification and capture. In short, there are

some species so awe-inspiring or meaningful that they hold magic.

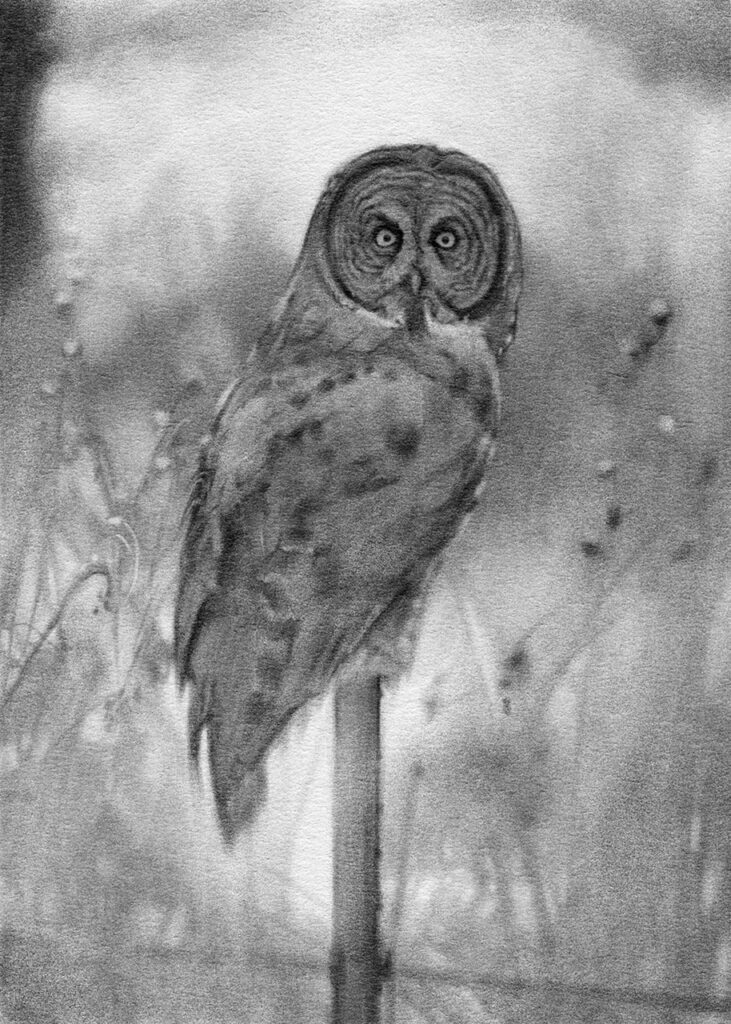

For me, that species is (or at least one of them is) the Great Gray Owl. I am a birder who has

seen nearly all of the expected species that occur in the US ABA area, and yet I have never

seen one of these. It is not a nemesis bird for me but one I have lacked opportunities for. I have

been birding so many amazing places in the world, but never have I been in the time and place

where one of these magnificent owls might be.

The scientific name for Great Gray Owl is Strix nebulosa, a name that not only connotes

mystery but also literally means obscure, misty, foggy, cloudy. It translates from Spanish and

Portuguese directly to nebula, and when you start thinking on those lines you are mentally

traveling very far indeed. Many of my birding friends have booked trips specifically to look for

these owls of the northern forest; there are well-known locations in the US and Scandinavia to

tick them. For U.S. birders, Sax-Zim Bog in Minnesota or Yosemite in California are great

places to start.

While one can look for these birds in reliable areas, I have a slightly different dream in mind. I

really want to find one while hiking in Yellowstone National Park in Montana. As a note to

birders for whom listing is of primary importance, this is not a recommended strategy for

finding them (see the previous paragraph). The owls are in the park, but they are scattered

across a very large amount of habitat, and their locations are variable from year to year and

generally not publicly shared when found. But the thing is, Yellowstone is also a life experience

for me, one my Montana-born mother told me childhood stories about. It is a place she dearly

loved, full of animals that she loved, and it is a place I wanted to drive her back to before she

passed away. Sadly, I did not have the chance. Yellowstone National Park is one of the last

national parks in the U.S. that I have not yet seen. In my dream, I am hiking in one of our

country’s most impressive natural spectacles, combining a lifer park with my most wanted lifer

bird, in a context of great personal significance. The bird would be self-found, of course

(grinning; why not shoot for the moon?).

Citation: Bull, E. L. and J. R. Duncan (2020). Great Gray Owl (Strix nebulosa),

version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology,

Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.grgowl.01