Starting point – The story so far…

In two previous blog posts, I presented the concept of the Custom Usability Index and described the preparation phase, where the usability categories are customized and weighted, in more detail. In this post, I would like to elaborate on the application itself, and explain the steps necessary to obtain a valid CUI evaluation in the end.

This is the starting point for our application example: We are developing a new web application for a business client. At the start of the project, the product owner in charge had the usability categories explained to them by a UX expert, and then defined the target states. Then, they prioritized the latter according to their requirements, laying the foundation for the regular rating of the future application using the CUI. After a certain period of development, the first release candidate has now been deployed to the QA system, ready for testing.

The Custom Usability Index (CUI) in action – Now your software is up to bat!

What do we do now? There are several different test methods for testing the 13 usability categories. The choice of the test method depends not only on its suitability for the respective usability category, but on numerous other factors as well. The availability of the end users, the know-how of the usability tester, and time and financial resources play an important role. In practice, the preferred scenario in which numerous end users are comprehensively tested by several usability testers with minute-keepers over an extended period of time, is rare.

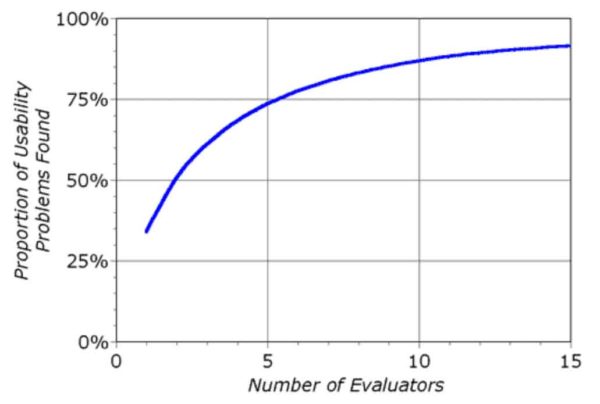

What do we forfeit by restricting the resources? Basically, accuracy and independence of the evaluation. But this is not the primary objective of the CUI. The tests, irrespective of their scope, are primarily supposed to identify problems and potential for improvement. That means that, even if the result of test A deviates from test B, the problematic issues are clear, enabling concepts for developing software with better usability. A resource-friendly method of testing is the heuristic evaluation. Heuristic evaluation is an inspection method where a group of usability experts check an application for compliance with specific guidelines and heuristics (in this case, the usability categories of the CUI adapted to the concept of use). According to Nielsen, approx. seven testers will find 80% of all usability errors; follow-up tests are less productive because few additional errors are identified.

In real-life agile software development projects, however, just getting several usability experts for the test is a rarity, which is why the evaluation is usually done by 1-2 experts. Depending on the complexity of the application and the scope of the documentation, a usability expert who is familiar with the application should be able to obtain a viable evaluation result within one to two days. This means that even with several “small-scale” usability tests, you can enhance the quality of your software and realize some improvements.

An example: Evaluation of 13 categories, 31 criteria “in a nutshell”.

Let us start with the category of effectiveness. The product owner defined the following target state for this category: “The user has access to the functions required for the completion of the tasks at all times, and reaches them in no more than two steps. In doing so, they are given no more than the information they need at the time (focus is to be on the data).”

Furthermore, effectiveness was weighted with the Fibonacci number 3.

The category of effectiveness comprises the criteria scope of functions and adequacy. For the “scope of functions” criterion, the different use cases of the web application have to be tested, and in addition, the tester has to check whether the required functions can be reached in no more than two steps.

The current release candidate fully meets the target state for this criterion, and consequently, it is awarded the maximum rating of five points.

Now for the second criterion of adequacy, which requires the user to be given no more than the information they need at the time, and the focus to be on the data.

Several minor anomalies cause a 2-point deduction, resulting in a rating of 3 points. Together with the rating of the scope of functions criterion, the average rating for the category of effectiveness is 4 points.

The other 12 categories and 29 criteria should be rated the same way as shown in the above example. As the complete documentation of an entire CUI test would go beyond the scope of this blog post, we are going to skip to the next step and take a closer look at the final calculation.

Example of a complete CUI calculation

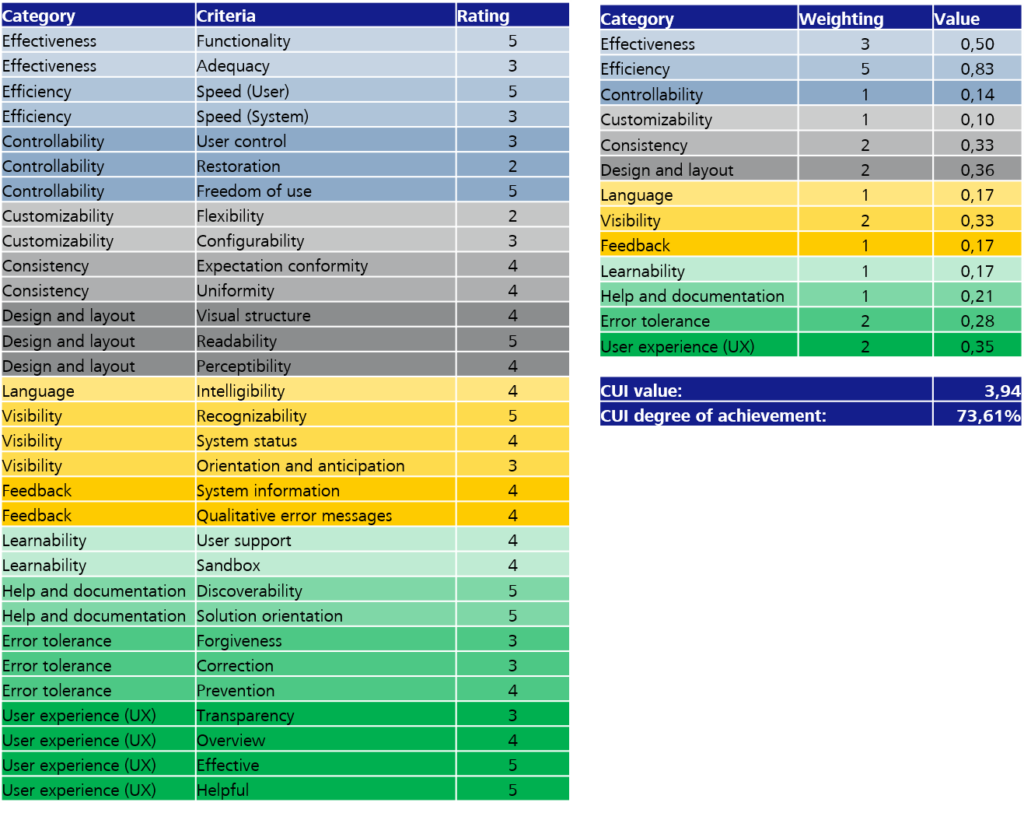

The table above shows a completed CUI calculation matrix after the completion of the test. The final CUI value is calculated as follows:

- Calculation of the average value of a category (sum of the ratings / number of criteria)

- Calculation of the relative weighting (weighting value of the category / sum of all weighting values)

- Calculation of the final category value (average value of the category * relative weighting)

- CUI value = sum of the final category values

- CUI degree of achievement = ((CUI value – 1) / 4)

Let’s run this calculation for our example:

- Rating of the effectiveness category (scope of functions 5 points + adequacy 3 points) / 2 criteria = 4 points

- Sum of the weightings of all categories = 24

- Relative weighting of the effectiveness category = 3/24 = 0.125

- Single value of the effectiveness category = rating of 4 * relative weighting 0.125 = 0.50

Hooray, it’s done! – Now what?

First of all: Congratulations for taking care of your users’ needs. Now, the following steps need to be taken:

- Develop possible solutions for the identified problems in the form of wireframes and prototypes

- Illustrate the effect of future user stories with respect to the different usability categories

- Question the specifications of your product owner… You are the expert!

- Actively present alternatives instead of unquestioningly implementing the specifications you are given

- Carry out further CUI tests at regular intervals, thus tracking the effect of the improvements and/or new specifications on the usability of your software

The Custom Usability Index allows you to obtain useful results with few resources. The lightweight method is smoothly integrated into the agile software development process and identifies flaws in your software. Regular tests enable long-term tracking and make usability truly comprehensible. Take the leap—your users will appreciate it!

Brief insight into usability tests in agile software development!