Like virtually all artifacts in software development, the style guide is also subject to continuous change. Nevertheless, traditional versions are frequently used today, even though technological progress has long since opened up new ways to bring traditional documents to life. This blog post addresses this issue, using the example of the style guide to show how its continuous development can improve the collaboration of designer and developer: Are living style guides the future of UI design?

Once upon a time… there was the document-based style guide

For a long time, the collaboration of the UX designer and the front-end developer was governed by an artifact: the document-based style guide. This style guide is typically created as follows:

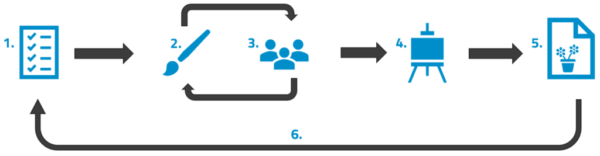

- First, a requirements analysis is done.

- The designer then creates mockups based on the requirements.

- The mockups are discussed with the client (x iterations) and finally approved.

- Then, the designer creates the agreed graphics with the design tool.

- The “style guide” document is compiled from the graphics and corresponding descriptions.

- In case of amendments, all these steps have to be repeated.

As a basis for communications, a good style guide should include the following points:

- Concept (application from the project’s perspective, product vision, UX objectives)

- Structure (structure of the application)

- Interaction design (design of the dialog between the user and the system)

- Color scheme (rules of use for colors)

- Typography (fonts and font sizes)

- Icons and graphics (overview of all icons and graphics of the application)

- Standard interaction elements (repeatedly used user interface elements)

- Special views (non-standard UI views and control elements)

- Language (communication style and wording)

- Multimedia (use of images, audio and video)

However, listing the standard interaction elements in particular in a rigid, document-based style guide is not ideal. Considering the number of different UI states such as hover, active, selected, etc. for each element, this list can easily grow to several pages. Few developers like to dig through pages and pages of documents; therefore, the risk of non-compliance with the style guide increases.

Furthermore, the traditional version of the style guide poses two problems: The rigid reference to a document which is often very long requires great imagination, and there is no possibility of interaction with the various elements.

Status quo & future of UI design… coming to life

There are several approaches for addressing the points of criticism described above. For example, the content of the style guide can be brought to life by means of a UI prototype kept and updated in parallel. This makes it possible to test the various states of the standard interaction elements in the context of the application, or also to represent special views in detail. With this “hands-on” mentality, the design requirements become clear more quickly, and the tedious rifling through style guide documents becomes unnecessary.

However, this solution does not eliminate the following issues: In everyday project work, the designer often creates templates that are too unusual and cannot be implemented with the applicable UI framework without significant additional effort. The limited range of functions of the prototyping tool is another problem. It is not always possible to simulate the final behavior down to the last detail, which can lead to false assumptions.

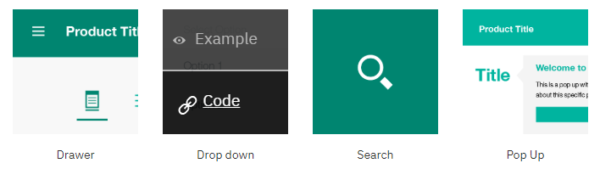

Therefore, the current trend is towards implementing the entire style guide as a separate “live” web application. This means that the elements are implemented in the actual application before use, and the developers only need to copy the source code.

Some useful references:

- IBM: https://www.ibm.com/design/language/

- Google (Material): https://material.io/

- Lonely Planet: http://rizzo.lonelyplanet.com/styleguide/

- Yelp: https://www.yelp.com/styleguide

- CodePen: https://codepen.io/guide

- Atlassian: https://atlassian.design/ & https://atlaskit.atlassian.com/

The benefits of this implementation are obvious: In addition to a clear structure of the necessary information and elements, maintainability in particular improves significantly. If a color has to be changed, this usually only means a change of the color code in the style sheet in the “living style guide”; whereas in the traditional, document-based style guide, countless paragraphs and designs have to be updated. Furthermore, the QA department can test the required behavior before the actual development starts. It is even possible for changes in the style guide to be adopted into the application immediately if both applications reference the same style sheet. This way, redundancies and inconsistencies can be excluded from the start. The level of integration of the style guide into the development process certainly depends on the project at hand, but the possibilities of optimization are limitless in this respect.

The “living style guide” has become all the rage, and it is used by numerous top IT companies such as Google or IBM. It continuously reduces the gap between design and development, and in the end, the one who profits the most is the user :-)!