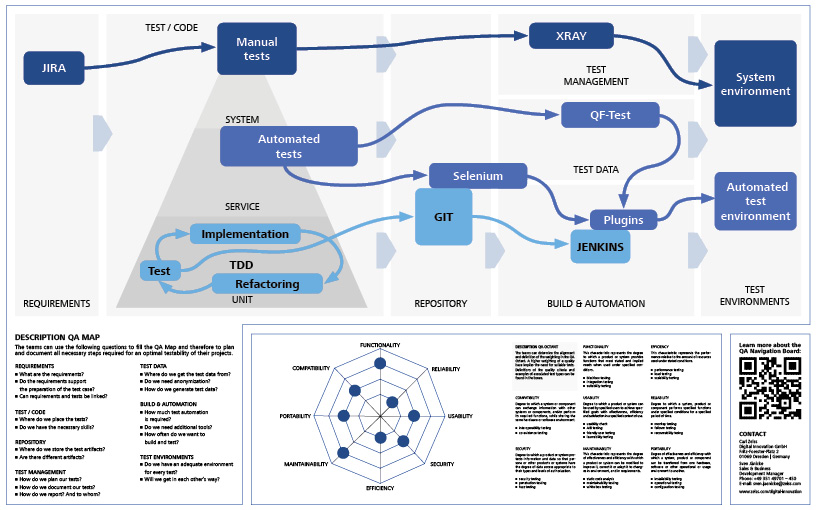

We would like to present our agile visualization tool, the QA battle plan, a tool that allows agile development teams to recognize and eliminate typical QA issues and their effects.

Like a wrong architectural approach or using the wrong programming language, the wrong testing and quality assurance strategy can result in adverse effects during the course of a project. In the best case, it only causes delays or additional expenses. In the worst case, the tests done prove to be insufficient, and severe deviations occur repeatedly when the application is used.

Introduction

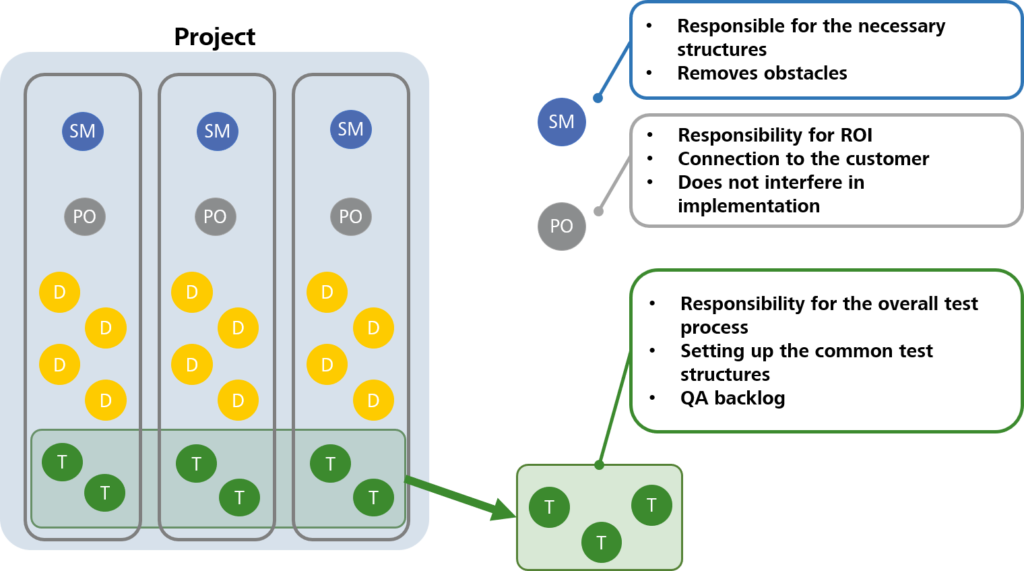

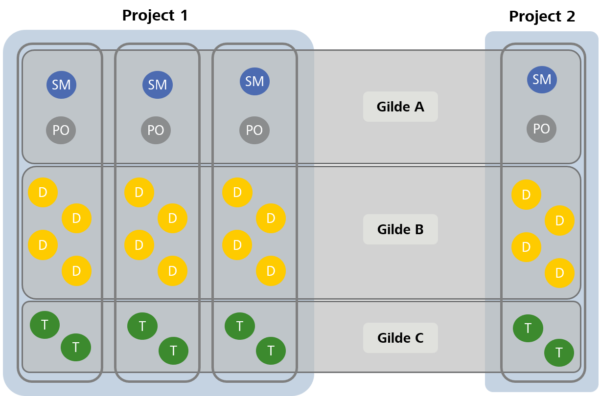

Agile development teams notice issues and document their effects in the Retrospectives, but they are often unable to identify the root cause, and therefore cannot solve the problem because they lack QA expertise. In such cases, the teams need the support of an agile QA coach. This coach is characterized on the one hand by his knowledge of the agile working method, and on the other hand by his experience in agile quality assurance.

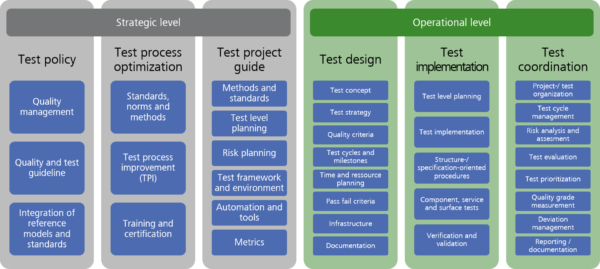

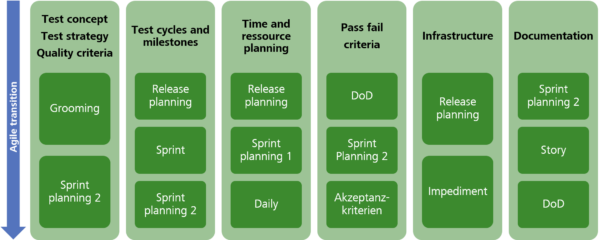

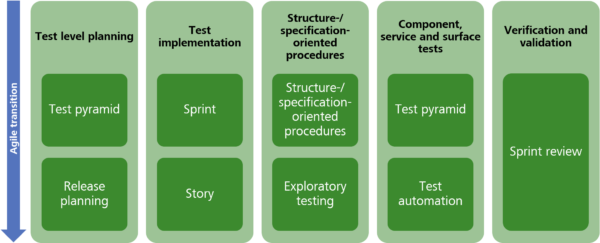

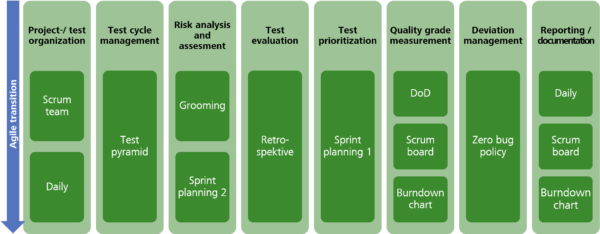

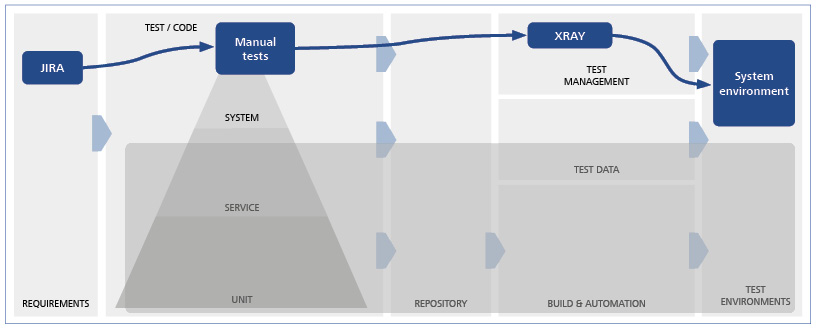

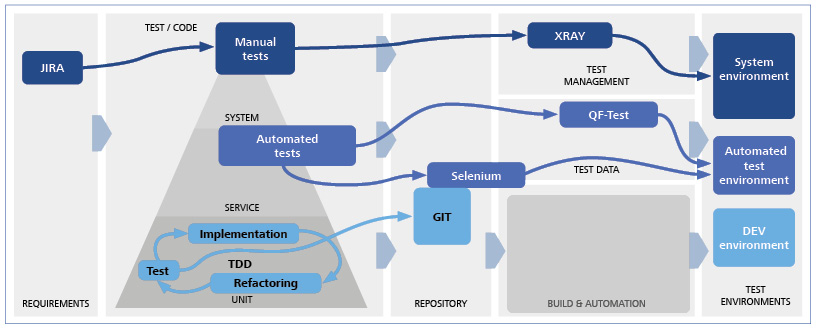

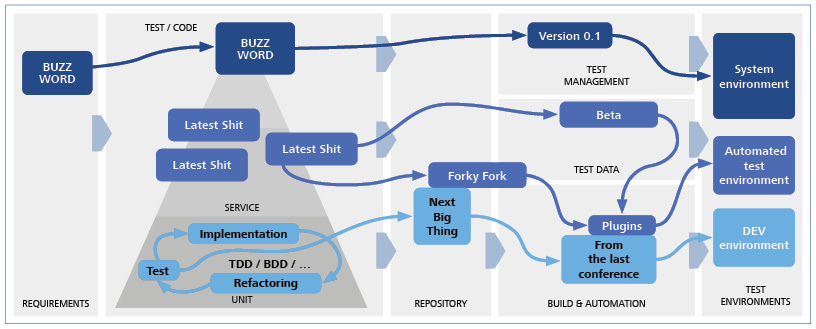

The first step in the agile QA coach’s work is recording the status quo of the testing methods of the agile development team. For this purpose, he will use the QA battle plan, e.g. within the framework of a workshop. The QA battle plan provides a visual aid to the development teams which they can use to assess the planning aspects of quality assurance. Throughout the project, the QA battle plan can also be used as a reference for the current procedure and as a basis for potential improvements.

Anti-patterns

In addition, the QA battle plan makes it possible to study the case history of the current testing method. By means of this visualization, the agile QA coach can reveal certain anti-pattern symptoms in the quality assurance and testing process, and discuss them directly with the team. In software development, an anti-pattern is an approach that is detrimental or harmful to a project’s or an organization’s success.

I will describe several anti-patterns below. In addition to the defining characteristics, I will present their respective effects. As a contrast to the anti-pattern, the pattern—good and proven problem-solving approaches—will also be presented.

The “It’ll be just fine” Anti-pattern

This anti-pattern is characterized by the complete lack of testing or other quality assurance measures whatsoever. This can cause severe consequences for the project and the product. The team cannot make any statement regarding the quality of their deliverables, and consequently, they do not, strictly speaking, have a product that is ready for delivery. Errors occur upon use by the end user, repeatedly distracting the team from the development process because they have to analyze and rectify these so-called incidents, which is time-consuming and costly.

| No testing | Effect | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| • There are no tests | • No quality statement | • “Leave quickly” |

| • Testing is done in the user’s environment | • Introduce QA |

The solution is simple: Test! The sooner deviations are discovered, the easier it is to remove them. In addition, quality assurance measures such as code reviews and static code analysis are constructive measures for consistent improvement.

The Dysfunctional Test Anti-pattern

ISO 25010 specifies eight quality characteristics for software: functional suitability, performance efficiency, compatibility, usability, reliability, security, maintainability, and portability. When new software is implemented, the focus is most often on functional suitability, but other characteristics such as security and usability play an important role today as well. The higher the priority of the other quality characteristics, the more likely a non-functional test should be scheduled for them.

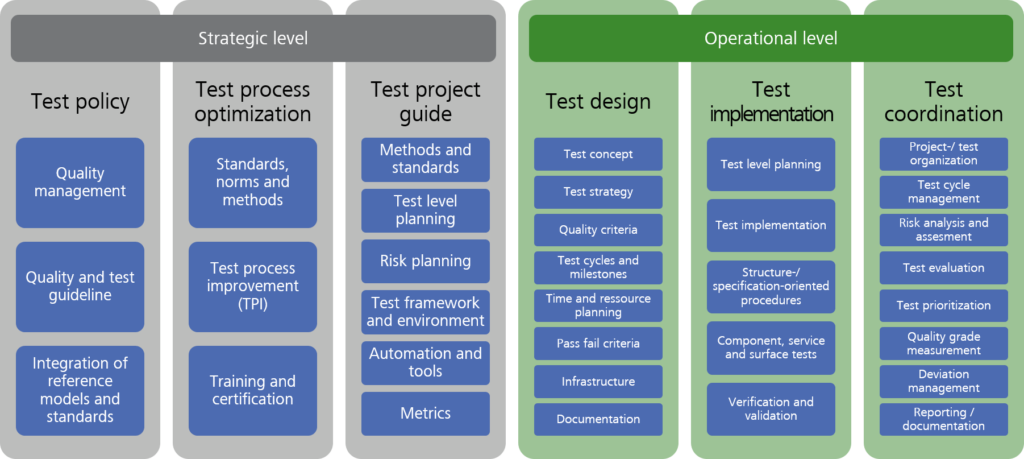

Therefore, the first question to be asked at the start of a software project is: Which quality characteristics does the development, and therefore the quality assurance, focus on? To facilitate the introduction of this topic to the teams, we use the QA octant. The QA octant contains the quality characteristics for software systems according to ISO 25010. These characteristics also point to the necessary types of tests that result from the set weighting of the different functional and non-functional characteristics.

| Functional tests only | Effect | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| • There are only functional tests | • No quality statement about non-functional characteristics | • Discuss important quality characteristics with the client |

| • It works as required, but… | • Non-functional test types | |

| • Start with the QA octant |

The Attack of the Development Warriors Anti-pattern

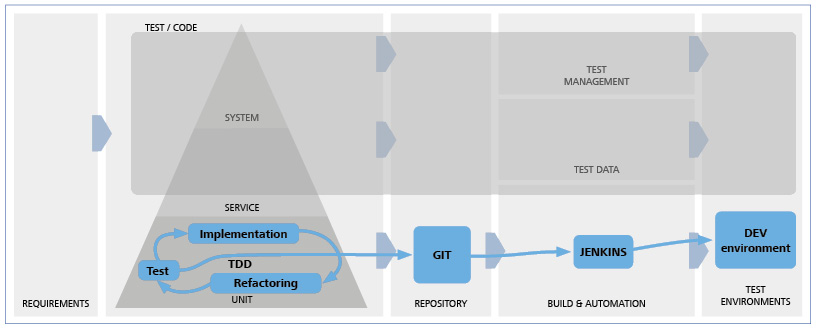

Many agile development teams—especially teams that consist only of developers—only rely on development-related tests for their QA measures. Usually, they only use unit and component tests for this purpose. Such tests can easily be written with the same development tool and promptly be integrated in the development process. The possibility to obtain information about the coverage of the tests with respect to the code by means of code coverage tools is particularly convenient in this context. Certainty is quickly achieved if the code coverage tool reports 100% test coverage. But the devil is in the detail, or in this case, in the complexity. This method would be sufficient for simple applications, but with more complex applications, problems arise.

With highly complex applications, errors may occur despite a convenient unit test coverage, and such errors can only be discovered with extensive system and end-to-end tests. And for such extensive tests, the team needs advanced QA know-how. Testers or trained developers have to address the complexity of the application at higher levels of testing in order to be able to make an appropriate quality statement.

| The attack of the development warriors | Effect | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| • Development-related tests only | • No end-to-end test | • Include a tester in the team |

| • No tester on the team | • Bugs occur with complex features | • Test at higher levels of testing |

| • 100% code coverage | • Quick |

The “Spanish Option” Anti-pattern

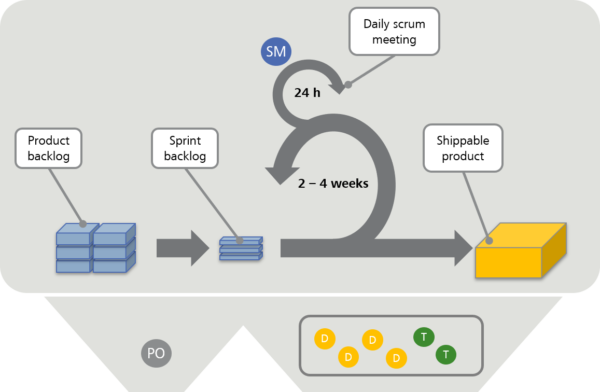

The time in which a function has been coded and is integrated into the target system is becoming ever shorter. Consequently, the time for comprehensive testing is becoming shorter as well. For agile projects with fixed iterations, i.e. sprints, another problem arises: The number of functions to be tested increases with every sprint.

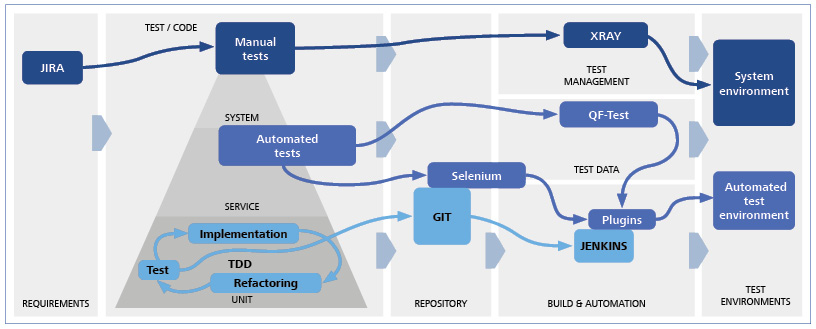

Plain standard manual tests cannot handle this. Therefore, testers and developers should work together to develop a test automation strategy.

| Manual Work | Effect | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| • There are only manual tests | • Delayed feedback in case of errors | • Everybody shoulders part of the QA work |

| • Testers are overburdened | • Test at all levels of testing | |

| • Introduce automation |

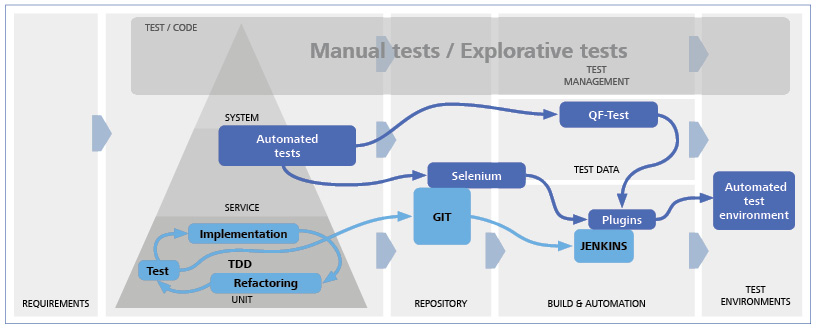

The Automated Regression Gap Anti-pattern

A project without any manual tests would be the other extreme. Even though this means a high degree of integration in the CI/CD processes and quick feedback in case of errors, it also causes avoidable problems. A high degree of test automation requires great effort—both in developing the tests and in maintenance. The more complex the specific applications, and the more sophisticated the technologies used, the higher the probability of test runs being stopped due to problems occurring during the test run, or extensive reviews of test deviations being required. Furthermore, most automated tests only test the regression. Consequently, automated tests would never find new errors, but only test the functioning of the old features.

Therefore, automation should always be used with common sense, and parallel manual and, if necessary, explorative tests should be used to discover new deviations.

| 100% test automation | Effect | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| • There are only automated tests | • Very high effort | • Automate with common sense |

| • Everybody is overexerted | • Manual testing makes sense | |

| • Build stops due to problems |

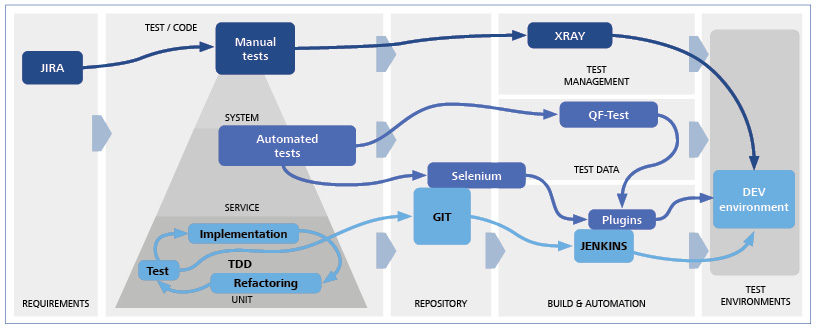

The Test Singularity Anti-pattern

Tests of different types and at different levels each have a different focus. Consequently, they each have different requirements regarding the test environment, such as stability, test data, resources, etc. Development-related test environments are frequently updated to new versions to test the development progress. Higher levels of testing or other types of tests require a steadier version status over a longer period of time.

To avoid possibly compromising the tests due to changes in the software status or a modified version, a separate test environment should be provided for each type of test.

| One Test Environment | Effect | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| • There is only one test environment | • No test focus possible | • Several test environments |

| • Compromised tests | • By level of testing or test focus | |

| • No production-related tests | • “One test environment per type of test” |

The “Manual” Building Anti-pattern

State-of-the-art development depends on fast delivery, and modern quality assurance depends on the integration of the automated tests into the build process and the automated distribution of the current software status to the various (test) environments. These functions cannot be provided without a build or CI/CD tool.

If there are still tasks to be done relating to the provision of a CI/CD process in a project, they can be marked as “to do” on the board.

| No Build Tool | Effect | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| • There is no build tool | • No CI/CD | • Introduce CI/CD |

| • Slow delivery | • Highlight gaps on the board | |

| • Delayed test results | ||

| • Dependent on resources |

The Early Adopter Anti-pattern

New technologies usually involve new tools, and new versions involve new features. But introducing new tools and updating to new versions also entail a certain risk. It is advisable to proceed with care, and not to change the parts/tools of the projects all at once.

| Early Adopter | Effect | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| • Always the latest of everything… | • Challenging training | • No big bang |

| • Deficiencies in skills | • Old tools are familiar | |

| • New problems | • Highlight deficiencies in skills on the board |